If you (or someone you care for) is preparing for—or already going through—recovery from parotid tumor surgery, it helps to know what’s “normal,” what tends to improve with time, and what deserves a call to your surgical team. Everyone’s case is a little different (tumor type, surgical approach, nerve involvement, other health conditions), but there are some common themes that can make the whole process feel less mysterious and less scary.

This guide follows the typical recovery journey and the questions patients often ask—especially about swelling, facial nerve symptoms, eating, and returning to daily life. I’ll keep it practical and patient-centered, and I’ll point out where your surgeon’s instructions should override general advice.

Understanding Parotid Tumor Surgery

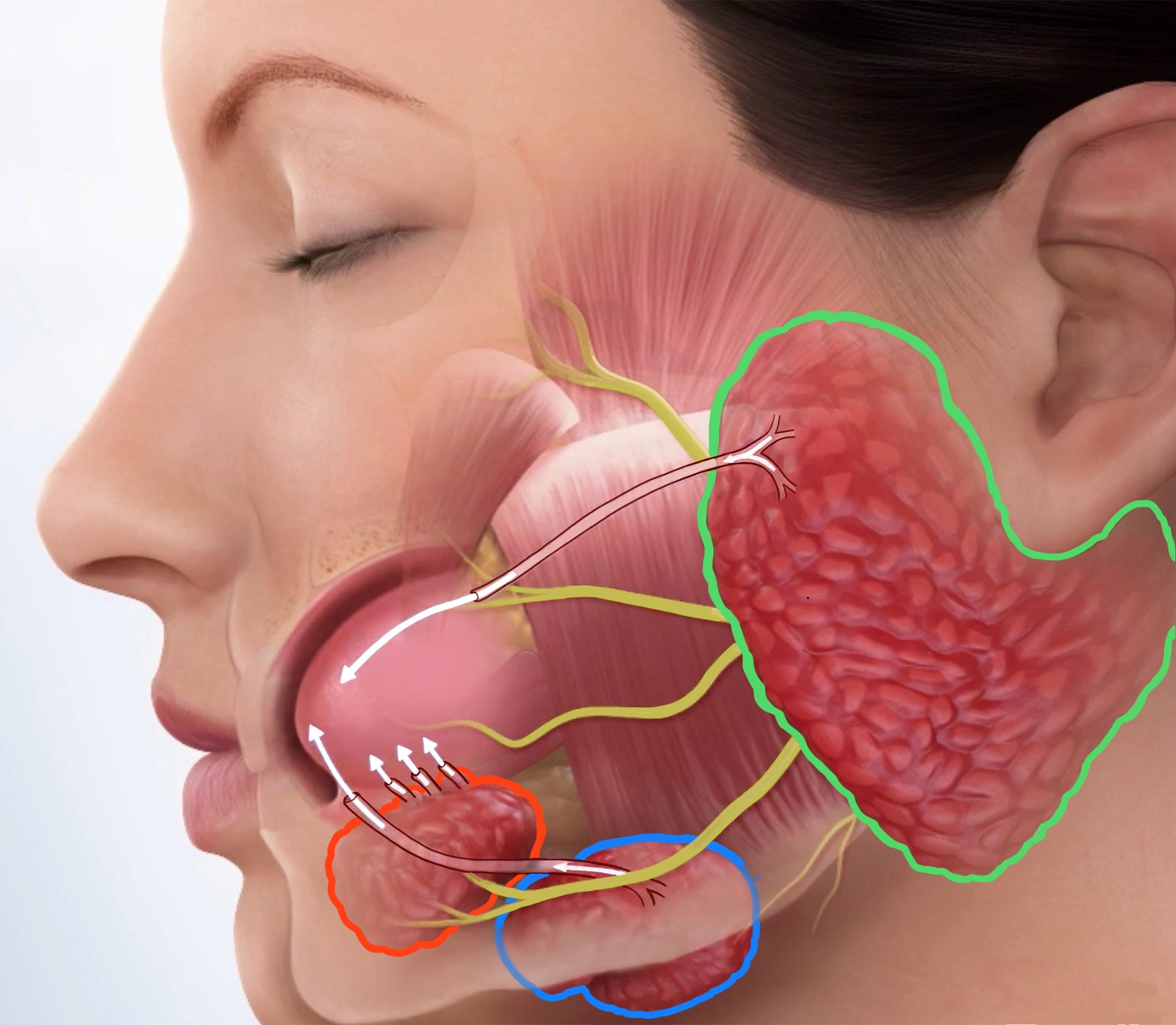

What is the parotid gland?

The parotid glands are the largest salivary glands. They sit in front of and just below each ear and help make saliva for chewing and swallowing. The big reason parotid surgery can feel intimidating is that the facial nerve—the nerve that controls many facial movements—runs through the parotid region. That’s why surgeons plan carefully around nerve location and function.

Why tumors form: benign vs malignant

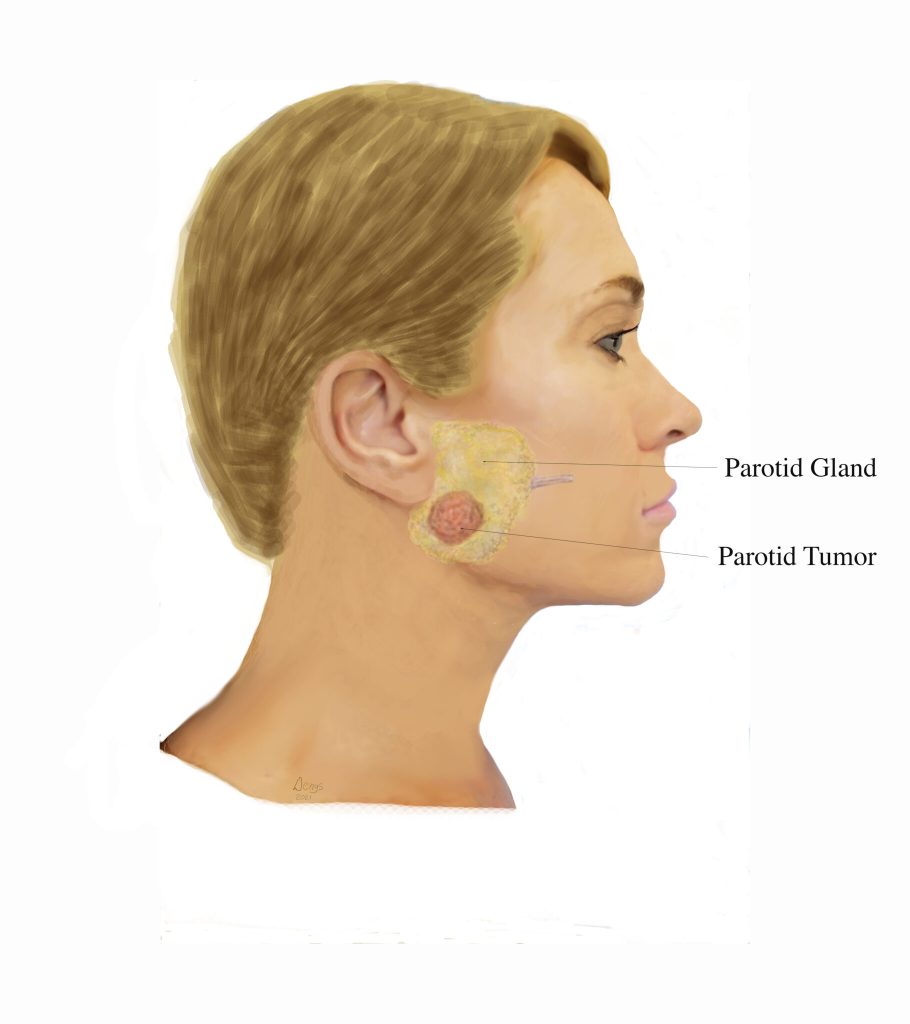

A “parotid tumor” simply means a growth in or near the parotid gland. Many parotid tumors are benign (noncancerous), but some are malignant (cancerous)—and imaging or a biopsy may not always give a final answer until the tissue is examined after removal. In medical teaching, a common rule of thumb is that most parotid tumors are benign, but the only thing that truly settles it is your pathology report.

You may hear specific names, such as pleomorphic adenoma or Warthin tumor for benign growths, and mucoepidermoid carcinoma among the more common malignant types.

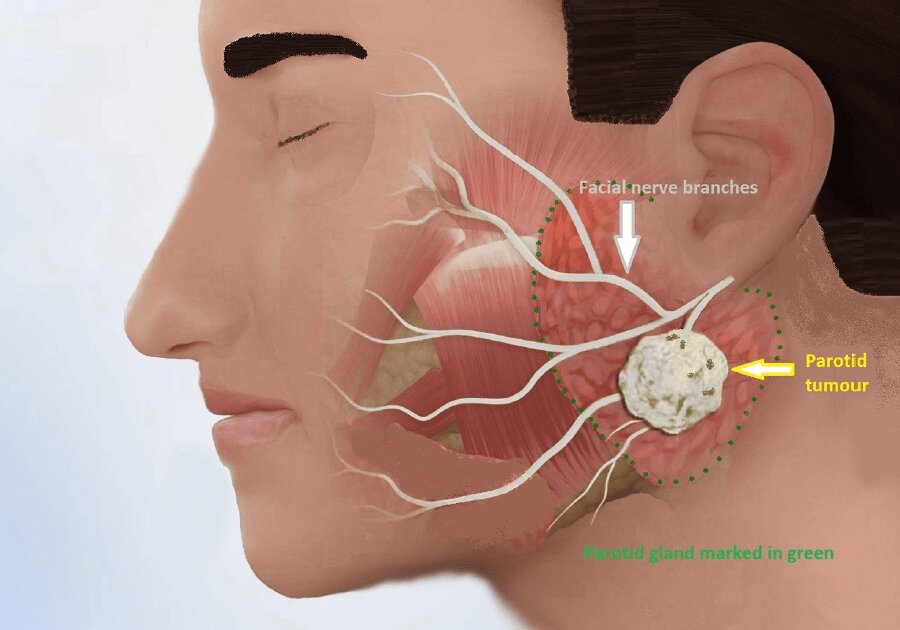

Types of parotidectomy: superficial vs total (and why it matters for recovery)

A parotidectomy is surgery to remove part or all of the parotid gland. The “type” mostly reflects where the tumor sits (more toward the surface vs deeper) and what’s needed to remove it safely.

Common categories include:

- Superficial parotidectomy: typically used when the tumor is in the superficial (outer) portion of the gland. The facial nerve is often identified and carefully dissected around.

- Total parotidectomy: used when the tumor is in the deep lobe or involves more of the gland. This can require more extensive dissection around the facial nerve.

- Radical parotidectomy (less common): may be needed when cancer involves the facial nerve, and the nerve can’t be preserved.

Why does this matter for recovery? In general terms, the more dissection around the facial nerve and surrounding tissues, the more likely you may experience temporary numbness, tightness, or weakness—and the longer it can take to feel “settled.”

Common reasons for surgery

Surgeons recommend parotid surgery for several reasons, including:

- removing a benign tumor that could grow or cause symptoms,

- removing a malignant tumor (or a suspicious growth),

- or removing disease that involves lymph nodes near the gland.

If you’re reading this after surgery, you may also be waiting on (or processing) pathology results. That waiting period can be emotionally heavy. It’s normal to feel anxious—even if your surgeon sounded reassuring. Later in this article, we’ll talk about what recovery can look like physically and mentally, plus how to support healing in a cautious, non-extreme way.

Immediate Post-Surgery Experience

This part of recovery is mostly about staying comfortable, protecting the incision, and letting the early swelling settle. It can feel intense for a few days—not always because of sharp pain, but because everything feels tight, numb, and unfamiliar.

In the Hospital

How long the hospital stay usually lasts

Some people go home the same day, while others stay overnight. It depends on things like your overall health, how extensive the surgery was, whether you have a drain, and how you’re doing after anesthesia.

Role of surgical drains

It’s common to wake up with a small tube (drain) near the incision. The purpose is to prevent fluid or blood from collecting under the skin while the area starts healing. Your team will tell you if it’s coming out before you leave or if you’ll go home with it for a short time.

If you do go home with a drain, you’ll typically be shown how to empty it and track the output, and when to call to schedule removal.

Initial pain management (and what “normal” feels like)

Many people describe the first day or two as more soreness, pressure, and tightness than severe pain. You may also have a scratchy throat from the breathing tube used during anesthesia. Your care team will provide pain relief and instructions for what to use at home.

Facial nerve monitoring

Because the facial nerve runs through the parotid region, the team pays close attention to facial movement. It’s normal for a clinician to ask you to smile, raise your eyebrows, or close your eyes after surgery to check function. Many centers also use facial nerve monitoring during surgery to help protect the nerve.

If you notice weakness right away, that can still be temporary—often related to swelling or the nerve being handled during surgery—and it may improve gradually with time.

First Few Days at Home

Once you’re home, your job is simple: rest, keep swelling down, take meds as directed, and watch the incision/drain.

Pain, fatigue, and occasional lightheadedness

Feeling very tired is common. Your body is recovering from both surgery and anesthesia. Resting (without staying completely still all day) tends to help most people feel steadier day by day.

If you feel lightheaded, it can sometimes be from not eating much, dehydration, or pain medicine. If dizziness is severe, sudden, or comes with other concerning symptoms, it’s worth calling your surgical team.

Swelling, numbness, and jaw stiffness

In the first several days, it’s common to notice:

- Swelling/puffiness around the incision

- Numbness (often around the ear or along the jawline)

- Jaw stiffness or discomfort when chewing

These can improve slowly rather than all at once. Numbness, in particular, may be one of the slower symptoms to fade.

Sleep posture advice (this helps more than people expect)

Many patients feel best sleeping with the head elevated for the first few nights to reduce swelling and pressure. A couple of pillows or a slightly raised bed angle is commonly recommended in post-op instructions.

If lying flat makes you feel short of breath or extremely tight in the neck, let your doctor know—especially if the neck looks very swollen.

Diet adjustments (soft foods first)

Chewing can feel awkward early on—partly from jaw stiffness, partly from swelling, and sometimes from mild facial weakness. Starting with soft, easy-to-swallow foods can make meals less stressful. Examples commonly suggested include yogurt, pudding, scrambled eggs, mashed potatoes, cooked fruit, smoothies, and other gentle foods, then advancing as tolerated.

A small tip that often helps: smaller bites, slower chewing, and sips of water between bites. If swallowing feels genuinely difficult (not just sore), tell your care team.

Activity basics (gentle, not intense)

Light walking is often encouraged to support circulation and reduce constipation, but most post-op guidance recommends avoiding strenuous activity and heavy lifting until your surgeon clears you.

Healing Timeline: Week-by-Week

Just keep in mind: your exact pace depends on the size/location of the tumor, how much tissue was removed, and how much the facial nerve had to be handled. So think of these as “most common patterns,” not strict rules.

Week 1–2: Acute Recovery Phase

Swelling, bruising, mild facial weakness

- Swelling often gets worse before it gets better. Many people notice peak puffiness around days 3–5, then a gradual settling.

- A lot of swelling improves by about two weeks, but mild fullness or “firmness” can linger longer (and sometimes fluctuates).

- Mild facial weakness can happen early on and may be related to swelling or temporary nerve “stunning.” It often improves gradually, but it can take months in some cases.

Drain removal and wound care

- Follow-up is commonly scheduled early. For example, Cleveland Clinic describes follow-up 1–2 days after surgery to remove a drain and 5–7 days to remove non-absorbable stitches (if you have them).

- Wound-care instructions vary based on what you have (skin glue vs stitches vs drain). Johns Hopkins notes that with stitches, ointment may be used until stitches are removed, and if you go home with a drain you may need to empty/measure it and arrange removal once output is low enough.

- Some guidance recommends keeping the wound dry for the first week, which is why showering and shaving often need extra care early on.

Activity restrictions

- In the first two weeks, most advice is “gentle movement, no strain.” Johns Hopkins specifically advises starting gentle stretching, but avoiding heavy lifting and strenuous activity for about two weeks (and then returning slowly).

- Many people also take at least a week off work, especially if they’re still tired, sore, or adjusting to eating/chewing comfortably.

Week 3–6: Subacute Recovery

This is the phase where you often feel “more normal,” but the area can still feel tight, numb, or oddly sensitive.

Scar healing

- Your incision is usually healing well on the surface by this stage, but scars keep changing underneath for months. It’s common for scars to look more noticeable early on and then fade over time.

- Many surgeons recommend silicone gel or silicone sheets to support scar appearance, and avoiding sun exposure / using sunscreen over the incision area.

- If your surgeon clears it and the skin is fully closed, scar massage is often introduced a few weeks after surgery (commonly around 2–3 weeks in general scar guidance). Don’t start if you still have scabs or open areas.

Gradual return to light activity

- This is when many people begin easing back into more regular routines—still listening closely to any pulling, throbbing, or swelling that ramps up after activity.

- A useful “rule of thumb”: if a walk or light chores make swelling noticeably worse that evening, scale back and build up more slowly.

Facial mobility exercises (if needed)

- If you have facial tightness or weakness, your surgeon may suggest gentle facial movements or refer you to physiotherapy. The goal is controlled movement, not forcing big expressions that strain the area.

Emotional impacts

- This is also when the mental side can show up: impatience, worry about the scar, anxiety while waiting for pathology results or follow-up scans, or just feeling “not quite like myself yet.”

- If you find yourself avoiding meals, social plans, or mirrors because of changes in facial movement or swelling, that’s very understandable—and it’s also worth mentioning at follow-up so your team can support you (sometimes small interventions help a lot).

After 6 Weeks: Longer-Term Recovery

Possible nerve regeneration / ongoing numbness or tingling

- By now, the biggest day-to-day discomfort is often gone—but numbness and nerve-related sensations can be the slowest to resolve.

- Cleveland Clinic notes it may take months up to a year for numbness or facial weakness to fully recover for some people.

- Cambridge University Hospitals also notes that when facial nerve weakness happens, it’s often temporary, but can take several months to recover fully.

Frey’s syndrome (sweating while eating)

- Some people develop sweating/flushing near the cheek/temple/ear when eating months later. Cleveland Clinic notes symptoms often develop within the first year, and commonly around 6–18 months after surgery (because nerves take time to regrow and sometimes “rewire” in an unhelpful way).

- Not everyone gets this, and when it happens it’s usually not dangerous—just annoying or socially uncomfortable. It’s treatable, so it’s worth mentioning to your clinician if it shows up.

Final cosmetic healing

- Even when you feel functionally fine, appearance continues to improve: scars often fade over several months, and the “settling” of contours can take time too.

Potential Complications to Watch For

Most people recover from parotid surgery without major complications. But there are some issues to be aware of—especially in the first few weeks—so you can spot them early and respond appropriately. Here’s a clear breakdown of what’s common and temporary, what’s less common but important to catch, and what’s worth asking your surgeon about during follow-ups.

Temporary vs Persistent Facial Nerve Palsy

Mild weakness—especially around the mouth, eyebrow, or eye—is fairly common right after surgery. This can happen even if the nerve wasn’t cut or damaged, simply because it was stretched, manipulated, or inflamed. The term for this is neuropraxia, and it often improves over weeks to months.

According to several surgical centers:

- Temporary facial palsy may resolve gradually over weeks or months.

- If the nerve was injured or removed due to cancer, long-term facial palsy may occur and require further treatment (such as physical therapy, or in rare cases, nerve repair procedures).

Most clinicians track facial movement at follow-up visits to see if function is returning.

Saliva Leaks and Sialocele

A sialocele is a pocket of saliva that collects under the skin if a salivary duct leaks or isn’t completely sealed after surgery. It usually feels like a soft, fluctuating swelling near the incision, and may appear days or even weeks after surgery.

- It’s not an infection, but it can be uncomfortable or interfere with healing.

- Treatment might include aspiration (draining it with a needle), pressure dressings, or sometimes temporary Botox injections to reduce saliva production until the tissue seals.

If your swelling increases after it had gone down, or if you feel a “bubble” under the skin that gets bigger when eating, call your surgical team. It might be a harmless sialocele—but worth checking.

Hematoma or Infection

While rare, these are early complications that often show up in the first 48–72 hours.

- A hematoma is a collection of blood under the skin. It tends to appear suddenly as firm swelling, often with bruising and pain. If it’s large or growing, it may require drainage.

- Infection typically involves redness, warmth, increasing pain, or discharge from the incision. You might also feel feverish or unwell.

Most infections are mild and treated with antibiotics, but early contact with your surgical team is key. Don’t wait if you notice significant changes in pain, drainage, or swelling.

Frey’s Syndrome (Gustatory Sweating)

As mentioned earlier, this is a delayed complication where the skin near the ear or cheek sweats or flushes when you eat, especially with spicy or sour foods.

- It’s not dangerous, but it can be socially bothersome.

- It usually shows up months after surgery—not right away.

- If it happens, your doctor may confirm it with a starch-iodine test, and treatments can include topical antiperspirants, Botox injections, or minor procedures to separate nerve pathways.

Scar Sensitivity or Tightness

Even a well-healed incision can feel tight, itchy, or oddly sensitive for weeks or months. This doesn’t always mean something is wrong—nerves regrow slowly and scars take time to soften.

Things that often help include:

- Silicone gel or sheeting to support soft scar formation

- Gentle massage once cleared by your surgeon

- Sun protection to prevent discoloration

- For discomfort, over-the-counter creams or topical steroids may be suggested

If your scar becomes increasingly firm, raised, or painful, ask about options like steroid injections or laser therapy.

How to Support Your Recovery Naturally and Gently

Your body does the bulk of the healing work on its own—but there are small, simple habits you can practice to support that process gently and safely. No need for extreme supplements, rigid routines, or expensive products. Instead, focus on comfort, consistency, and common sense.

This section offers practical suggestions drawn from post-surgical care principles, not medical guarantees. Always check with your surgeon before starting new routines, especially if you’re still healing.

Gentle Movement

Light activity supports circulation, reduces stiffness, and helps prevent complications like constipation or blood clots.

- Short walks around your home or neighborhood are usually encouraged once you’re steady on your feet.

- Avoid high-impact or strenuous activities (running, heavy lifting, intense workouts) until your doctor gives the go-ahead—typically a few weeks post-op.

- If you notice swelling worsens after movement, scale back and build up more gradually.

Moving helps—but listen to your body, not the clock.

Supportive Rest

Rest is not the same as lying down all day. Good healing rest includes:

- Elevated sleep posture (with pillows or a wedge) to reduce swelling in the neck/face during the first week or two.

- Short naps if you’re fatigued, especially in the first days after anesthesia.

- Avoiding pressure on the surgical side while sleeping, at least until tenderness and swelling go down.

Try to balance rest with a little movement during the day so you don’t feel stiff or sluggish.

Nutrition and Hydration

You don’t need a “special diet” for healing—but hydration and gentle nourishment make a big difference.

- Soft foods are easiest in the first week—think soups, smoothies, mashed vegetables, stewed fruits, scrambled eggs, well-cooked rice, and yogurt.

- Drink plenty of water or herbal teas, especially if you’re on pain medication (which can cause constipation).

- Try to include protein in your meals to support tissue repair—like lentils, tofu, eggs, chicken, or soft fish (when chewing feels OK).

- Avoid anything that makes chewing painful or opens your jaw too wide too soon.

Healing can slow if you’re undernourished—so even small, frequent meals help if your appetite is low.

Jaw Stretches (Only When Ready)

If your surgeon gives the green light, gentle jaw mobility exercises can help with tightness. These are often introduced 2–3 weeks post-op, not right away.

A common approach involves:

- Opening the mouth slowly and comfortably, then relaxing

- Moving the jaw gently side to side

- Practicing soft chewing with more variety as tolerated

Never force your mouth open. Progress is gradual, and some asymmetry or stiffness is normal for a while.

Stress Regulation

Surgery recovery isn’t just physical—it affects your mood, sleep, confidence, and sense of control. Healing often feels slower than expected, which can lead to frustration or worry.

Helpful calming habits include:

- Breathing exercises (even just a few minutes a day)

- Listening to calming music or nature sounds

- Spending time in natural light during the day to support sleep cycles

- Journaling, art, or low-pressure hobbies that don’t strain your body

Give yourself permission to rest without guilt. Your nervous system heals better when you’re not in survival mode.

What About Herbal or Natural Remedies?

If you’re interested in traditional or herbal approaches:

- Focus on gentle, food-based herbs (like ginger tea for nausea or turmeric in cooking).

- Avoid anything that thins the blood, stimulates the immune system heavily, or interacts with medications, unless cleared by your doctor.

A respectful approach is best: healing blends modern care with traditional wisdom cautiously.

When to Seek Medical Advice and What Questions to Ask at Follow-Up

Knowing when to call your surgical team can give you peace of mind—and might prevent small issues from becoming bigger ones. This section offers a simple guide to what’s worth watching, plus useful questions to bring up at your follow-up appointment.

Signs You Should Call Your Doctor

Most post-op symptoms improve gradually. But call your surgeon if you notice any of the following:

1. Sudden swelling or firmness near the incision

- Especially if it feels tight, warm, or rapidly growing—could be a hematoma, sialocele, or infection.

2. Redness, heat, or pus-like drainage

- Mild pinkness can be normal, but increasing redness, foul odor, or yellow/green discharge deserves attention.

3. Fever over 38°C (100.4°F)

- A low-grade temperature can happen post-op, but persistent or high fever could suggest infection.

4. Significant facial weakness

- Some mild weakness is common. But if you develop new or worsening droop, trouble closing the eye, or drooling, especially after initial improvement, call promptly.

5. Trouble swallowing or breathing

- Rare, but urgent. If swelling makes it hard to breathe or swallow, seek emergency care.

6. Clear fluid leaking from the incision or swelling that increases while eating

- Could be a saliva leak or sialocele—not an emergency, but needs evaluation.

7. Pain that gets worse instead of better

- Discomfort is expected, but worsening pain after several days may signal infection or other complications.

Questions to Ask at Follow-Up

Your post-op visit (usually within 1–2 weeks) is a good time to get clear on:

- What did the pathology report show?

- Were the margins clear? Was the tumor benign or malignant?

- If I have facial weakness now, what is the expected recovery timeline?

- Should I do facial or jaw exercises—and when?

- When can I return to work or normal activities?

- What can I do to help the scar heal well?

- What follow-up schedule should I expect (especially if it was cancer)?

- What symptoms should prompt a call between now and the next visit?

It helps to write questions down beforehand and take notes during the appointment—or bring someone with you to help listen.

Final Thoughts

Parotid surgery recovery isn’t just about getting through the first week. It’s about gradually regaining comfort, confidence, and clarity—over weeks or even months. Some parts heal fast (like swelling), while others (like nerve sensitivity or scars) may shift slowly. That’s normal.

You’re not alone in this, and there’s no “right” speed to heal. Be patient with your body, ask questions when you’re unsure, and give yourself time to feel like yourself again.

Natural support like buah merah or ant nest plant may be part of the picture, but it’s not a substitute for medical guidance.