When people first hear about the “myrmecodia,” they usually have the same reaction: Wait—ants live inside it? And yes, that’s basically the point. This is one of Southeast Asia’s most unusual forest plants, and it has become widely discussed in herbal circles—often right alongside searches like Best juice for cancer or even miss-typed queries like Symptomps of high blood presure, where people are clearly looking for natural support options but aren’t always sure where to start.

Just to set expectations early: in traditional herbal contexts, this plant is often used as a supportive remedy, but it should not be treated as a replacement for medical care—especially for serious conditions.

What is the myrmecodia?

The “ant nest plant” most commonly refers to plants in the Myrmecodia genus—especially Myrmecodia pendans—which is frequently called sarang semut in Indonesia. Botanically, Myrmecodia is part of the Rubiaceae family (the same larger plant family that includes coffee and gardenias).

What makes it so distinctive is its growth form:

- It is an epiphytic plant, meaning it often grows on tree branches or trunks for support rather than rooting in soil like most plants do. It’s not a parasite—it uses the tree like a “platform,” not a food source.

- It forms a swollen, tuber-like base (often called a caudex or tuberous stem). Inside this swollen structure, the plant naturally develops tunnels and chambers.

- Those chambers become living space for ants, which is why it’s often grouped as an “ant plant” or myrmecophyte (plants that live in close association with ants).

Where it grows (and why Papua is often mentioned)

Myrmecodia species are found across Indochina and the broader Malesia/Papuasia region, including places like Papua and nearby rainforest zones. This tropical distribution is one reason the plant is strongly associated with eastern Indonesia in popular herbal storytelling and local trade.

In rainforest canopies, nutrients can be scarce—especially for epiphytes that aren’t rooted in rich soil. That’s where the ant partnership becomes important.

The “mutual benefit” in simple terms

Think of the swollen tuber as a natural apartment complex:

- The ants get shelter (and often a stable nesting site above the ground).

- The plant gets nutrients over time from ant waste and organic debris that accumulates in specific chambers. Some chambers are rougher and used like “waste rooms,” and the plant can absorb nutrients from what decomposes there.

This relationship is one big reason researchers find Myrmecodia interesting—not just as a plant, but as an ecological system.

Why people connect it with “herbal benefits”

In Indonesia, sarang semut is widely discussed in relation to its secondary metabolites (natural plant compounds). Several academic and review sources describe Myrmecodia extracts as containing groups of compounds such as polyphenols, including flavonoids, tannins, and other constituents that are commonly studied for antioxidant or antimicrobial activity in lab settings.

That said, lab findings don’t automatically translate into guaranteed outcomes for real people. In herbal education, the responsible takeaway is: this plant is traditionally valued and scientifically interesting, but it should be approached as a complementary option—especially if someone is dealing with complex health issues.

Why Is It Called the “Ant Nest” Plant?

The nickname comes from the plant’s built-in “rooms”—hollow spaces (called domatia) inside its swollen base where ants naturally move in and set up a colony. This plant–ant partnership is so common in the tropics that scientists group these as ant-plants or myrmecophytes. In plain language: the plant offers housing, and the ants “pay rent” in ways that can help the plant survive in a tough canopy environment.

The plant–ant relationship (the simple version)

- The plant provides shelter: those internal chambers are protected and stable, like a nest site up off the ground. (That’s the “ant nest” part.)

- The ants contribute nutrients: ants leave behind nitrogen-rich debris and waste in certain chambers, and ant-plants can absorb nutrients from that material through specialized linings or roots inside the domatia. This nutrient pathway is sometimes described as myrmecotrophy (plants being “fed” by ants).

- The ants can also defend the plant: many ant–plant relationships include protection from herbivores, plus ants clearing away competing growth nearby, which can indirectly help the plant access light and space.

How this helps the plant’s growth (especially as an epiphyte)

A lot of ant-plants—including Myrmecodia species—live as epiphytes, perched on branches where there’s limited soil and fewer steady nutrient sources. In that setting, having ants bring in organic material from a wider area can function like an “extra nutrient delivery system,” helping the plant persist where a typical root system might struggle.

How the structure concentrates nutrients

Not all chambers are the same. Research on ant-plant domatia shows that nutrients can move from domatia inhabitants (ants and other organisms living inside) into nearby plant tissues—basically, the plant is positioned to take advantage of whatever decomposes in those protected spaces.

This is one reason you’ll often see cross-sections of the tuber in educational images: the maze-like interior makes it obvious why people started calling it an ant nest.

Why researchers care (ecology first, “medicinal” second)

Ecologically, ant-plants are fascinating because they show how plants can evolve specialized structures to partner with insects—and how that partnership changes nutrient flow and survival in the rainforest canopy. That’s the core scientific interest: mutualism, nutrient cycling, and adaptation.

In herbal discussions, this ecological story sometimes gets mixed into health narratives—especially when people are searching during vulnerable moments (for example, someone might Google herbs during Recovery from parotid tumor surgery). If that’s you, it’s worth holding two truths at once: traditional plants can be meaningful support, but serious conditions need a clinician’s guidance so you don’t accidentally interfere with recovery, medications, or nutrition.

The same caution applies if you have complex metabolic issues—people may type something like diabetes mellitus hyponatremia while searching for natural options, but electrolyte and glucose balance are not areas to experiment without professional support.

Traditional and Indigenous Uses

Where these uses come from

In Indonesia, sarang semut is discussed both as a forest plant with a unique ecology and as a traditional remedy. Ethnobotanical writing has documented use among Dayak communities (for example, Dayak Ngaju in Central Kalimantan) as part of local “obat tradisional” (traditional medicine) practices.

In Papua and West Papua, it’s also widely talked about as a plant gathered from forest areas and sold in local markets as dried pieces or powder.

It’s important to frame this properly: traditional use is real cultural practice, but it’s not the same thing as clinical proof. The most respectful approach is to describe what communities use it for and how they prepare it—without turning that into a medical promise.

What it’s traditionally taken for (in everyday language)

In traditional discussions, people commonly reach for ant nest plant as supportive help for things like:

- Inflammation and aches (including sore joints and general “pegal-pegal”)

- Fatigue / low stamina and feeling “run down”

- Urinary discomfort and general internal complaints

- “Tumor/cancer symptoms” in the sense of folk belief and supportive use alongside medical care (not a stand-alone cure)

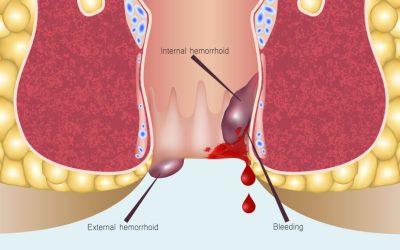

You’ll see similar themes echoed in research summaries that describe traditional use for conditions like ulcers, hemorrhoids, and other internal complaints, and note the plant’s popularity in herbal settings.

A gentle reality check: people often go searching for herbs during stressful health seasons—whether that’s scrolling “Best juice for cancer” lists late at night, or trying to make sense of body signals like Symptomps of high blood presure. Those are moments when support matters, but so does safe decision-making: it’s worth treating traditional herbs as complementary and keeping your doctor in the loop.

How it’s prepared in traditional practice

Across many Indonesian herbal products, the most common approach is straightforward:

- Dried slices, boiled into a tea/decoction. Many sources describe locals using dried parts of the plant by boiling them in water and drinking the resulting herbal water.

- Dried/powdered forms that can be brewed like tea or packed into capsules. This matches how the plant is now sold in modern herbal markets: as dried chips, powder, or capsule products.

Traditionally, preparation is often described as “simple and patient”: rinse, boil or steep, and drink warm. Taste-wise, people often describe it as earthy and woody—more like bark tea than a fruity drink.

Cultural notes worth keeping in mind

- Knowledge is local. How the plant is gathered, dried, and served can vary across islands and communities. “Sarang semut” is a broad market name, and different regions may refer to different Myrmecodia species.

- Respect and sustainability matter. When demand rises, wild harvesting can become intense. If you choose to use it, it’s worth thinking about sourcing that doesn’t encourage overharvesting or habitat damage (especially for epiphytic plants that depend on forest trees).

A safety-minded aside (because real life is complicated)

If you’re dealing with complex issues—say you’re in Recovery from parotid tumor surgery, or you’re juggling lab results related to diabetes mellitus hyponatremia—that’s exactly when you should be extra cautious with herbs. “Natural” can still interact with medications, appetite, digestion, and hydration. The safest move is to treat this as a discussion to have with your clinician, not a self-directed experiment.

Health Benefits and Active Compounds

Let’s be clear from the start: the ant nest plant (Myrmecodia pendans) has become popular in wellness discussions because of what researchers have found inside it—not because of some magical story about ants. While the plant–ant relationship is fascinating, what gets attention in modern herbal use is its chemical composition, especially in the tuber.

That’s where the story of potential “benefits” begins.

What researchers have found inside the plant

Multiple studies have reported that sarang semut contains a variety of secondary metabolites—naturally occurring compounds that plants produce as part of their survival strategy (to defend against pests, attract pollinators, or deal with stress). In herbal use, these compounds are often the ones studied for potential bioactivity.

Here are some of the key groups reported in Myrmecodia extracts:

- Flavonoids: These are antioxidant compounds found in many plants. They’ve been studied in the lab for potential roles in anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial activity. In traditional thinking, this is part of why the plant is believed to help with aches or infections.

- Tannins: Known for their astringent properties, tannins can affect digestion and have been investigated for potential antimicrobial effects.

- Phenolic compounds: These overlap with flavonoids and are widely studied for antioxidant activity.

- Glycosides and saponins: These are other plant defense compounds with possible immune-modulating or hormone-related activity in lab tests.

Some lab studies have also explored whether Myrmecodia extracts show activity in cell cultures—particularly with tumor lines. However, these are early-stage studies and don’t translate directly to human outcomes. That’s why even if you’ve seen people online calling this the “best juice for cancer,” it’s wise to interpret that as supportive tradition or personal hope rather than clinical truth.

Lab studies: cautious interpretation

A few academic reviews have reported in vitro (test tube) activity that could support the plant’s traditional use for inflammatory, metabolic, or infectious complaints.

For example:

- Some studies found antioxidant activity, which may support the body’s ability to handle oxidative stress (a general process involved in aging, inflammation, and disease).

- Other small-scale studies tested extracts against microbes or cancer cell lines, observing growth inhibition under specific lab conditions.

Again, that doesn’t make this a cure or treatment—it means there’s research interest. And in the world of herbs, that’s an important distinction.

Is it safe?

Safety information is limited, especially in terms of long-term human use. Most traditional use reports describe short-term, moderate consumption—like boiling a few grams of dried tuber to make tea, not high-dose extraction. If you’re pregnant, nursing, or on medication, you should speak with a health provider before trying any new herb.

This is especially true if you’re already managing something complex like diabetes mellitus hyponatremia, where fluid balance, blood sugar, and medication schedules can all interact. Even a mild herb can affect your routine in subtle ways—so it’s smart to loop in your care team before making changes.

How to Prepare and Consume It Safely

In traditional Indonesian herbal practice, simplicity is key—and the same goes for preparing sarang semut. The goal isn’t to turn it into an exotic tonic, but to respect the way it’s been used for generations: slow, gentle, and consistent, with the plant serving as part of a broader lifestyle of care.

Here’s how most people prepare and use it.

1. Boiled decoction (the traditional method)

This is the most common preparation, and still the most popular way to use it in households across Papua and Kalimantan.

Steps:

- Rinse a handful (about 3–5 grams) of dried ant nest tuber slices.

- Place in a small pot with about 2–3 cups of clean water.

- Bring to a boil, then simmer gently for 15–30 minutes.

- Strain and drink warm, usually 1–2 times per day.

Taste: Earthy, bitter, slightly woody—similar to bark teas.

Note: People often combine it with other traditional herbs like ginger or lemongrass to mellow the flavor. Some even treat it like a companion to natural juices—especially when searching for options like Best juice for cancer or “natural drinks for stamina.” But it’s important to remember: tea is not a juice, and the effects aren’t instant.

2. Powdered form

Some markets sell the dried plant already ground into powder, which can be brewed like tea or placed into empty capsules.

- For tea: Use ½ to 1 teaspoon of powder per cup of hot water. Let it steep 10–15 minutes before drinking.

- For capsules: Follow package instructions or consult a qualified herbalist. Most traditional use is tea-based, not high-dose capsules.

3. Ready-to-use products

In modern herbal markets, especially in Indonesia, sarang semut is now available as:

- Dried slices (in plastic pouches)

- Fine powder (in jars or sachets)

- Capsules (sometimes blended with other herbs)

If you’re trying these forms, the safest approach is:

- Start low, go slow.

- Check your sources. Make sure you’re getting the right species (Myrmecodia pendans), and ideally from sustainable harvests.

- Avoid mixing with medications without checking.

When to avoid or pause use

Certain situations call for more caution—or skipping altogether:

- During recovery periods (such as after surgery, illness, or trauma), unless cleared by a healthcare provider. For example, if you’re in recovery from parotid tumor surgery, your body needs stable support, and new herbs may complicate things.

- If you’re managing blood pressure or electrolyte disorders, like symptomps of high blood presure or diabetes mellitus hyponatremia. This is because herbal teas can influence hydration, blood volume, and digestion—all things that matter in these conditions.

General safety guidelines

- Not for children or pregnant women, unless part of a traditional family routine and approved by a knowledgeable elder or healthcare provider.

- Not a substitute for medication. Herbs can support, not replace.

- Watch for reactions. Even mild herbs can cause sensitivity in some people—especially if taken with other herbs, supplements, or prescriptions.

Conclusion: What to Remember

The ant nest plant—sarang semut, or Myrmecodia pendans—is a remarkable piece of rainforest ecology. It’s more than just a strange tuber filled with tunnels; it’s part of a living partnership between plant and ant, showing how life adapts in complex tropical environments. That alone makes it a species worth noticing.

But what brings it into kitchens, marketplaces, and conversations is something else: its long-standing role in traditional herbal practice. Across regions like Papua and Kalimantan, people have turned to this plant for generations—not as a miracle, but as a supportive daily herb to help the body cope with fatigue, aches, and internal imbalances.

Modern interest has only grown, especially among those looking for gentle, plant-based options during difficult health seasons. It shows up in online searches beside phrases like Best juice for cancer, or gets mentioned during moments of concern, like when someone’s dealing with symptomps of high blood presure or needs to be mindful of diabetes mellitus hyponatremia. These searches reflect hope, and a desire for healing—but they also remind us to be cautious.

If you’re curious about trying sarang semut, here’s what to keep in mind:

- Use it respectfully. This is a traditional plant, not a trend.

- Start small. Boil it gently, sip slowly, and listen to your body.

- Be cautious if you have health conditions. Especially after surgeries (like recovery from parotid tumor surgery) or if you’re on regular medication.

- Ask questions. A trusted herbalist or doctor can help you explore this safely.

Nature offers many quiet forms of support. Myrmecodia or sarang semut is one of them—an odd-looking tuber with a hidden world inside, shared between plant and ant. In the right context, with patience and respect, it may offer you something gentle and grounding too.